Liturgy For Wholeness

The following is an excerpt from Reb Zalman’s recent Ohalah talk focusing on the upcoming New Year. Click here to hear his singing of the traditional Hebrew nusach / melodic theme of the Remembrance (Zichronot) section from Rosh Hashanah Mussaf set to his English translation. Scroll down to the bottom where you will find his translation. Gabbai Seth Fishman, BLOG Editor:

Each year, on Rosh Hashanah, we touch upon three themes of the holiday: Malkhiyot / Kingship, Zichronot / Remembrance, and Shofarot / Blasts of the ram horn. There are special challenges we face with each one, which we will need to address so we can get our prayer to the place it needs to get.

Malkhiyot / Kingship presents difficulties for us connecting, in general, [because of our histories with democracy and monarchy], and it is all the more difficult, especially now. Imagine if you were introduced to the current melech / ruler of this country; could you say the bracha / blessing [for meeting a ruler] which goes, … Baruch atah … shenatan mik’vodo l’bassar vadam / who has given of Your glory to humans? So there are problems. How can we deal with the issue of kingship today and get beyond it for the davvenen we’ll need to do?

And Zichronot / Remembrance offers some problems, too. There are times when we are dealing with memory with honoring [good things that were]. But there are also those memories that sit with us [that are not so good]: trauma, stress, the holocaust years: These haunt us, and we have to be able to get rid of the toxic and negative ballast of some memories too. So we have to get past this too.

And Shofarot / the blowing of the shofar is the third theme and it’s touching to people. From the phrase, ki chok l’Yisrael hu / it’s a chok for Jews, we learn an important part of shofar, [namely, that it is a chok].

Note: A chok is a mitzvah / religious obligation for which there is no intuitive or rational understanding; we follow it, but we can’t explain why we are commanded to do so. Shofarot is one of these.

In 1973 I led a service in San Francisco. At the time, there were no prayerbooks available which I could use [because of things lacking in the translations]. Much of the material I used was in hashir v’hashevach.

These were days when we, in Jewish Renewal, were still testing out things and experimenting. I wanted to make sure we would be able to daven / worship in Hebrew and in English at the same time. (If you have a chance, get a copy of the audiotape I recorded in stereo, with Hebrew for one ear, and English for the other, to be listened to simultaneously… Davvening with Reb Zalman: An Audio Siddur, available from Aleph. It was a worthwhile experiment.)

There is something about the Hebrew flow of words and the melodies that go along with them that touches something that is deep and archaic in us.

Typically, the English was translated by people who were focusing on producing something for the head to process. I remember one time, with disdain, when I led the congregation in New Bedford using the Birnbaum prayer book and we were reading responsively in English and my line came up, “And thou hast exalted my power like that of the wild ox.” The translation didn’t have any respect for what the metaphor was trying to say; it was aimed at doing literal translation and nothing more. Then there were [other Siddurim whose authors] wanted to make it fancy and give it an almost Episcopalian feel, [using words like] “vouchsafe” and “bestow.” There were very few translations one could sink into with one’s heart and it’s still true to this day.

Also it’s necessary to be able to use the nusach [even if one davvens in English] which touches something much deeper than the cortex.

The English is necessary [for most congregations, so that the power of the text will be accessible to them]. And with the right kind of nusach, it’s impactful on the

people.I don’t like it when we constantly push niggunim / melodies with Hebrew phrases on congregations with people who are not able to read Hebrew and which they don’t quite understand! For this reason I’ve done all this vernacular work.

Before I used the vernacular prayers in English with my congregation, I used to davven for forty days in English myself so that I could feel unselfconsciously able to face God in English. If you are a congregational leader, please dare to try it out on yourself first, before using it on others. If you don’t try to sell it to yourself, if you are not secure with it, the other people will also feel insecure doing it.

Regarding the niggunim / melodies, I want to say that this time, during the High Holidays, we have to address some very deep and primitive places of our psyche. This is why our use of the traditional nusach [is so essential]. Skarbovve is a word for this. It is translated in Weinreich’s Yiddish dictionary as routine, but the word is derived from “sacre beau,” it is a sacred and a beautiful nusach. I feel many people who lead services jump into Shlomo niggunim, because they are well received and get a fast, positive response; but it’s not quite the right feeling for Rosh Hashanah. Something more has to happen on Rosh Hashanah than what you would do on a happy Friday night, with dancing around. It’s true that a little of this may be good at the end of even the first evening, to give people a sense they’re moving into a new year and they’re going to the apple and the honey. But there’s also the part of the momentousness and the awe, and that which takes people to a higher vibratory level and that can’t be missed. This is really what this is supposed to be.

So for those of you who will lead services, if you are using some of the simple melodies, please also use the nusach and bring people to that. There are deeper layers that awaken the ancestors within us. Although they may be archaic, think about what archaic does: It takes us back even to the limbic system, and to the reptilian system, and to the place where we are animal, the place where we are vegetable, the place where we are mineral, and all of this takes us back to the holistic whole being in the presence of God.

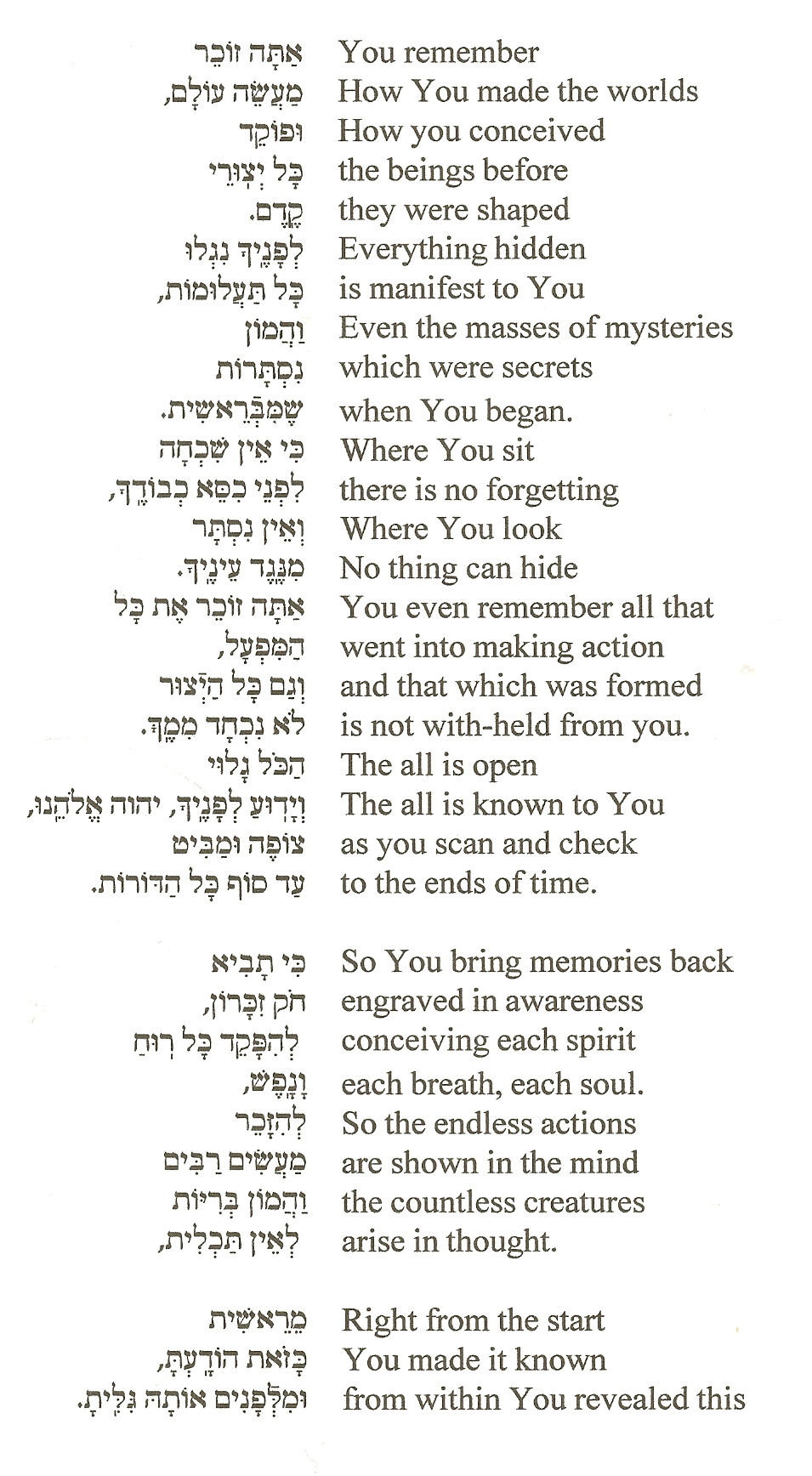

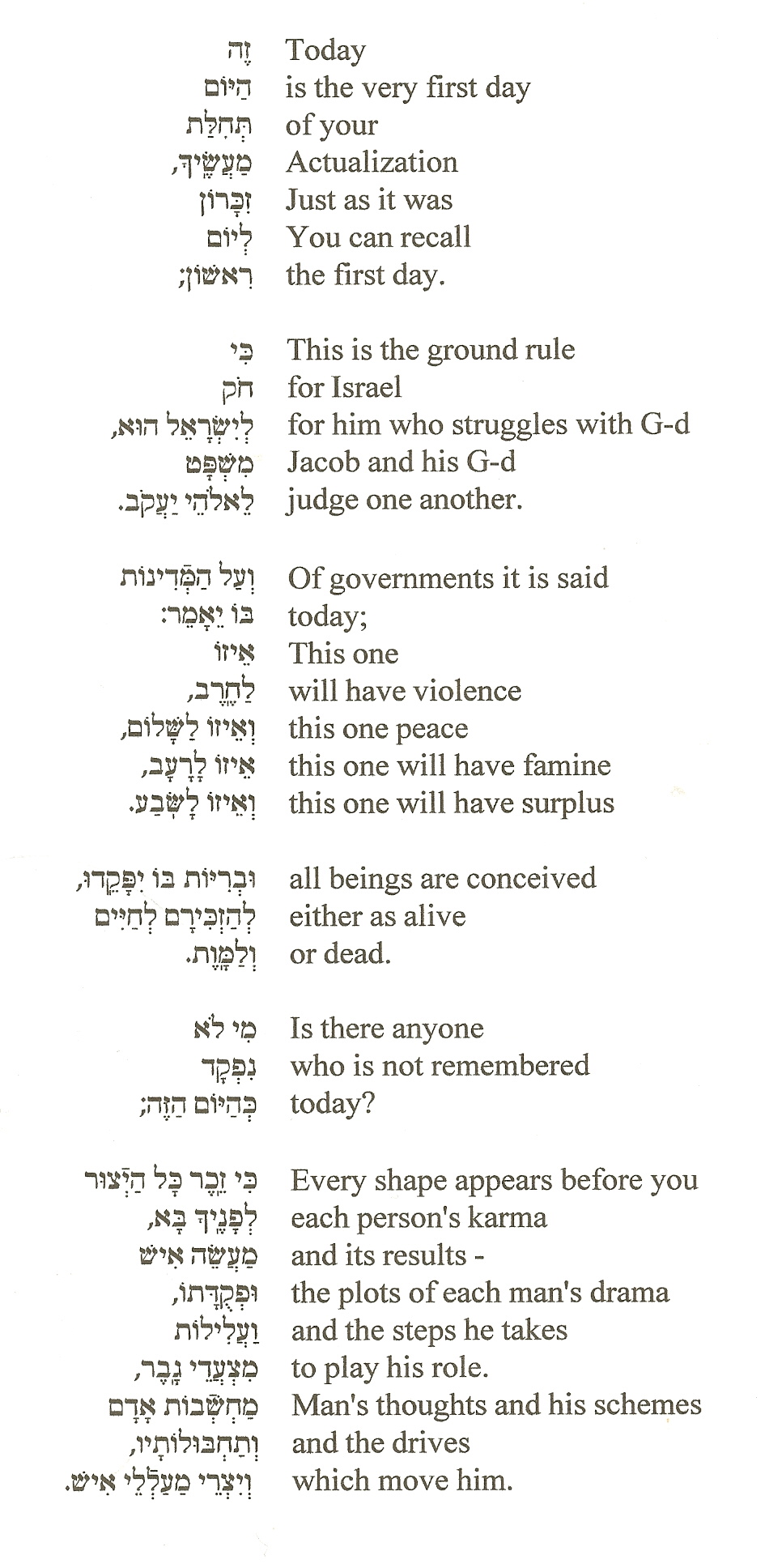

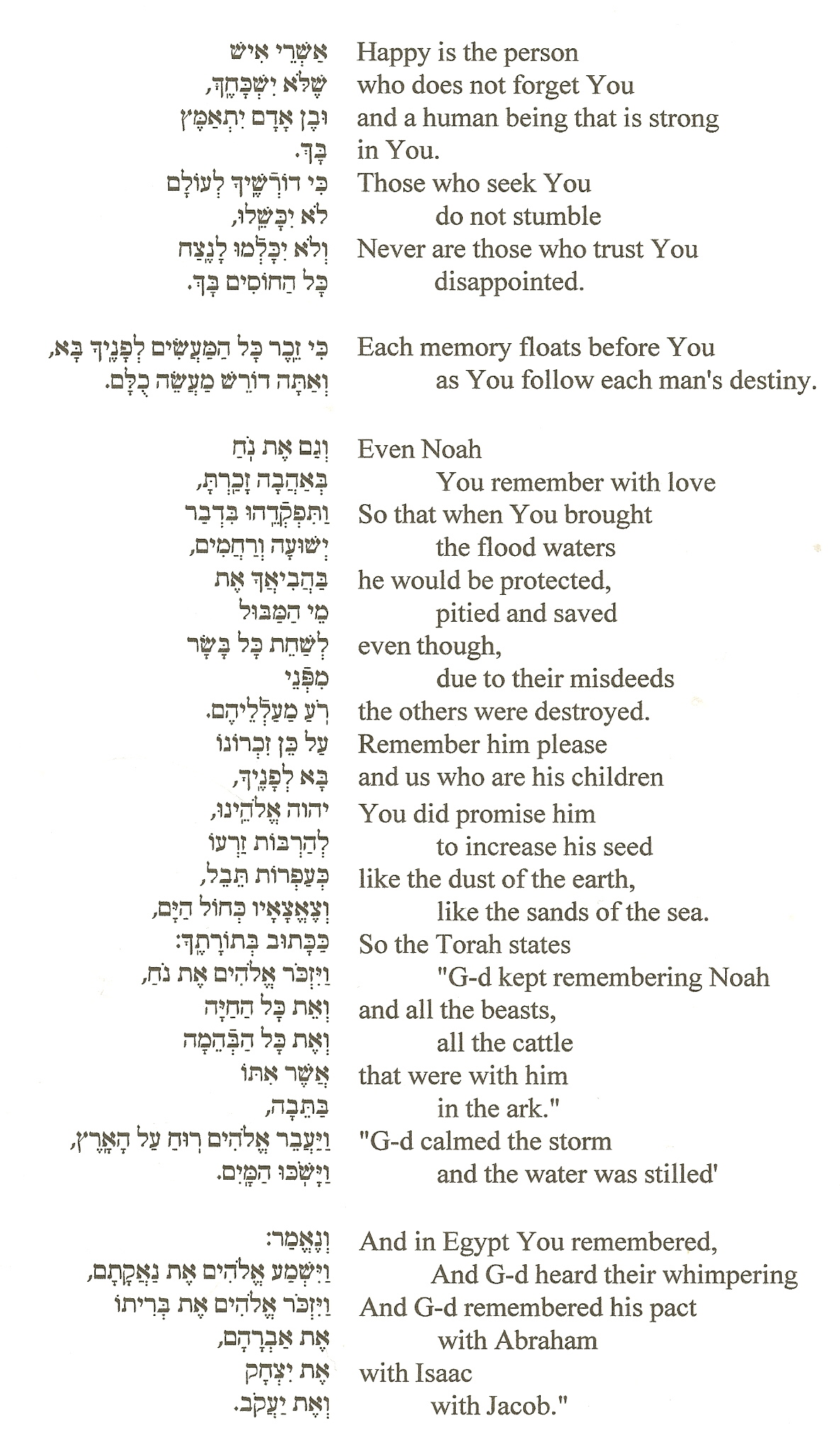

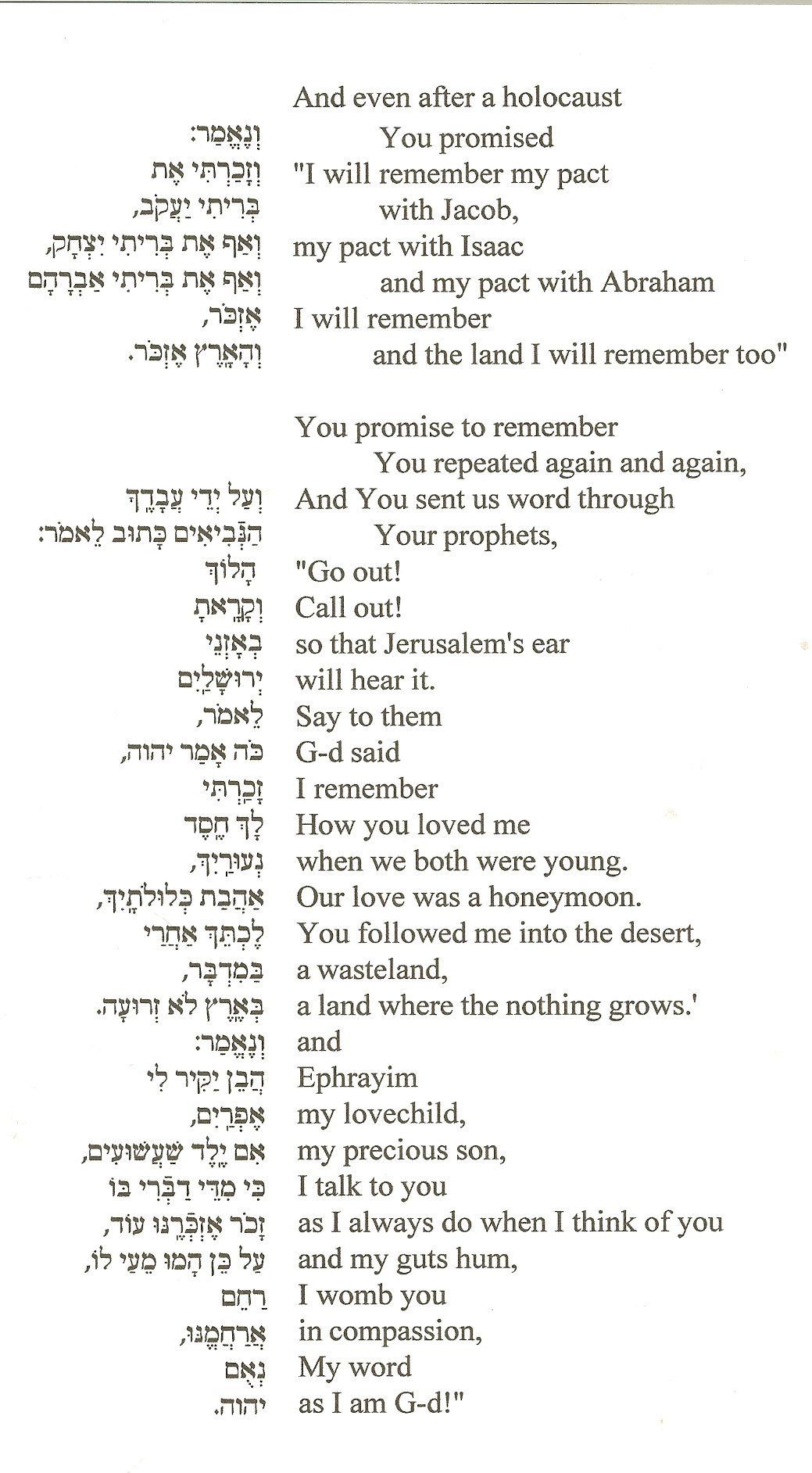

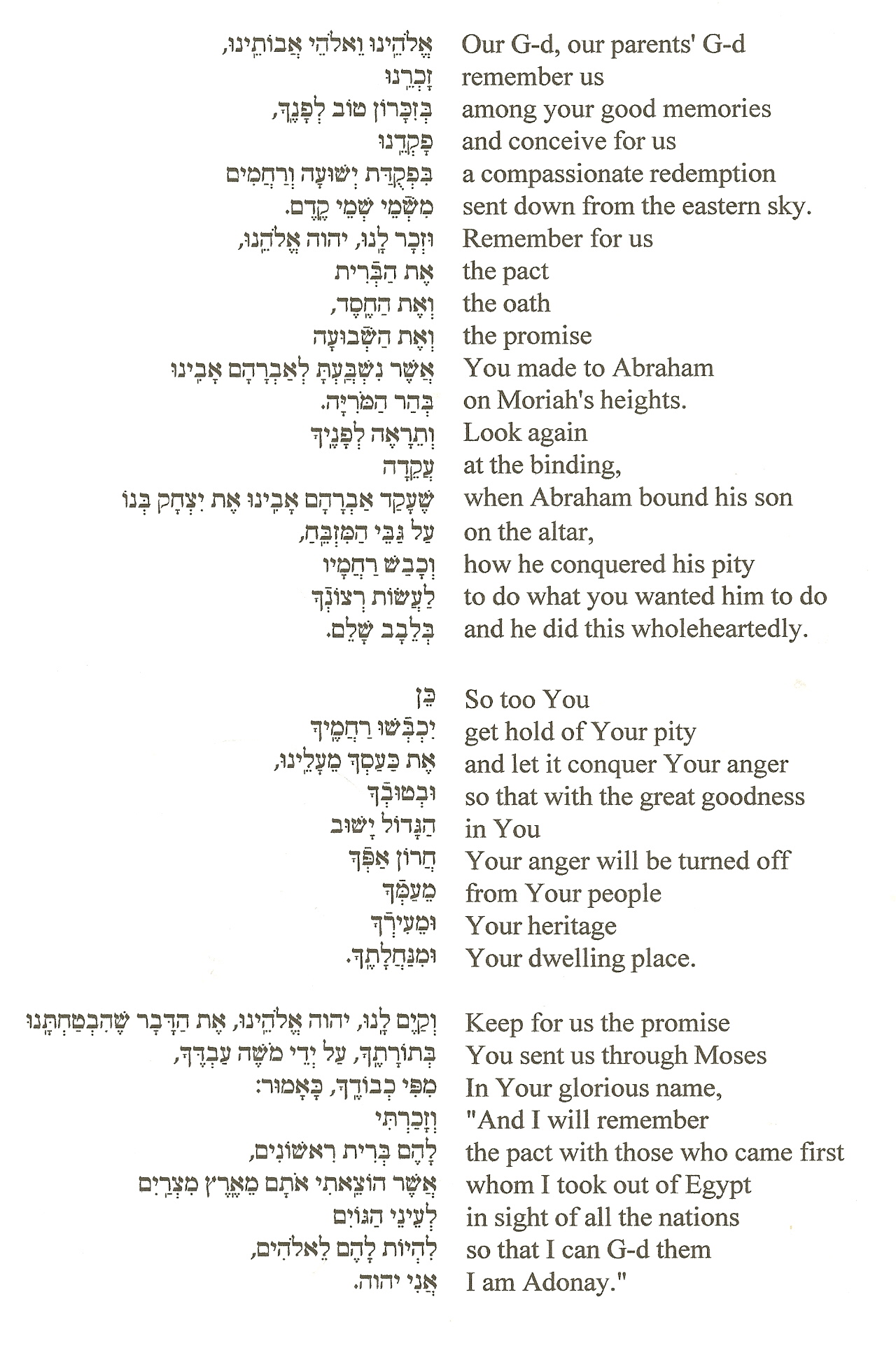

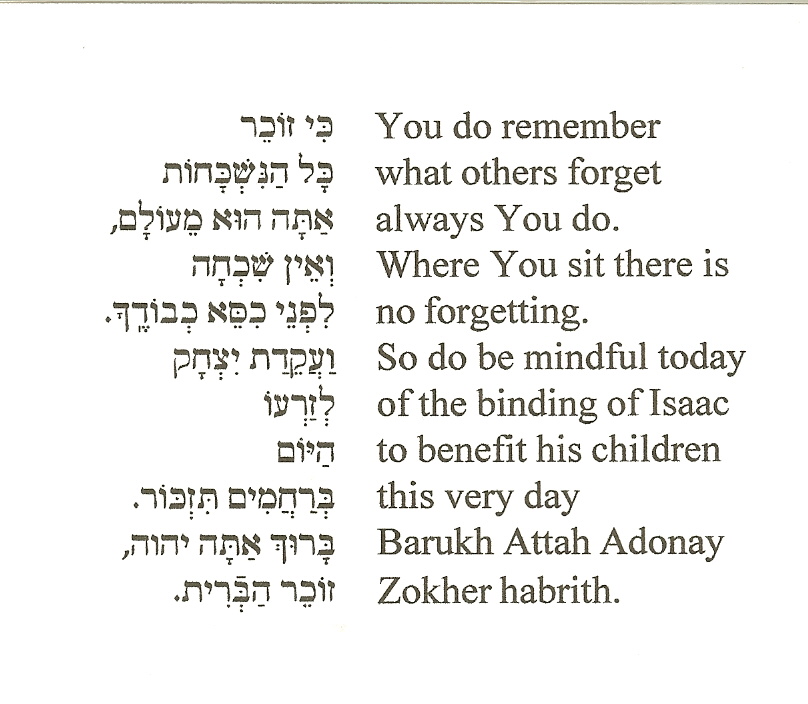

Please read below Reb Zalman’s translation of zichronot which conveys the meaning of the original Hebrew without leaving the heart behind.

September 12th, 2008 at 3:34 pm

Thank you for putting this out on the web. The singing Hebrew melodies in English translations is a huge bridge for the kahal and Reb Z’s translations make it easy to open new realms to those gathered. Even those brand new to davvenen can connect, participate and be nourished!

Shabbat Shalom,

Much Love,

T’mimah

September 16th, 2011 at 3:16 pm

Thanks again, this is relevant every year.

This year, I am thinking of offering some of the words for a RH drash to help the Kahal connect with a true essence of these unique teachings.

Shanah Tova

Much Much Love